Review of Spiders and Their Kin

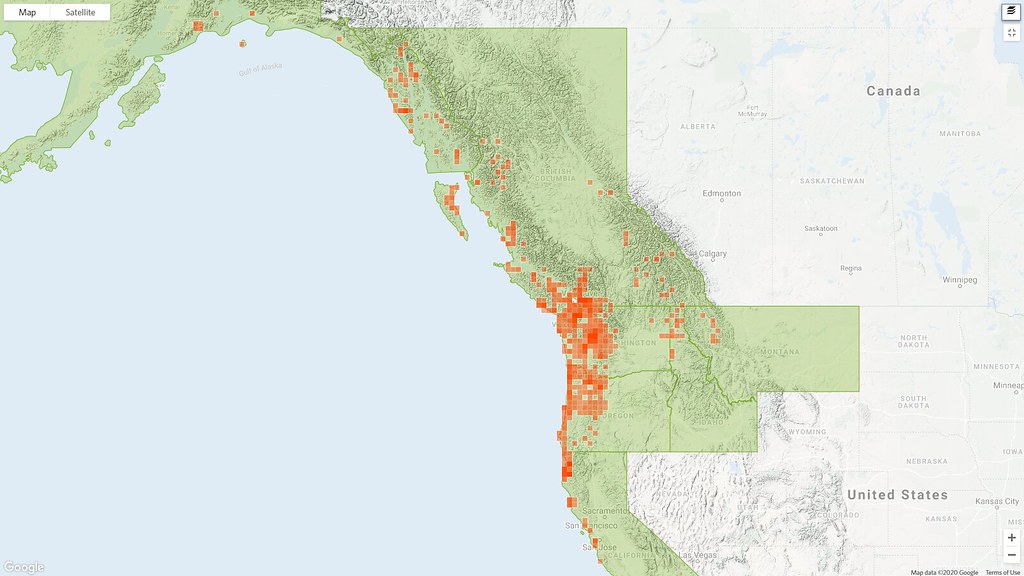

I found an interesting spider up on Mount Rainier a few years ago. The pale blue egg sac caught my attention. I guessed it was in the wolf spider family, roaming around at 1800 meters (6000 feet). I snapped a few photos and continued on to botanize.

A few months later, I added an observation on iNaturalist . I know this was a wolf spiders (Lycosidae) but not much more. After a few hours, @kathleendobson suggested this spider was in genus Pardosa. Recently (March 2023), @arachnologus (Rod Crawford ) confirmed the ID at the genus level and noted that in Western Washington, only this genus has blue egg sacs. I then asked Rod about how to get to a species level ID. He provided a detailed answer: "... For example, the female above has the pattern of the P. nigra species group and could be any of 3 species on Mt.Rainier. The best thing with an adult female is the almost-impossible closeup of the underside of the abdomen! However, this can potentially be done with a transparent container, but it has to be really close and really in focus."

I asked Rod to recommend a good beginner's book on spiders. He suggested Spiders and Their Kin by H. W. Levi et al. I ordered a copy of the book, and when it arrived, I noticed it was a Golden Guide, which I had thought of as a children's book. I was wrong! This book was a perfect introduction. It covers land arthropods other than insects, including spiders, scorpions, harvestmen, mites, centipedes, millipedes, and wood lice. The book starts with the classification, anatomy, and behavior of spiders and their kin.

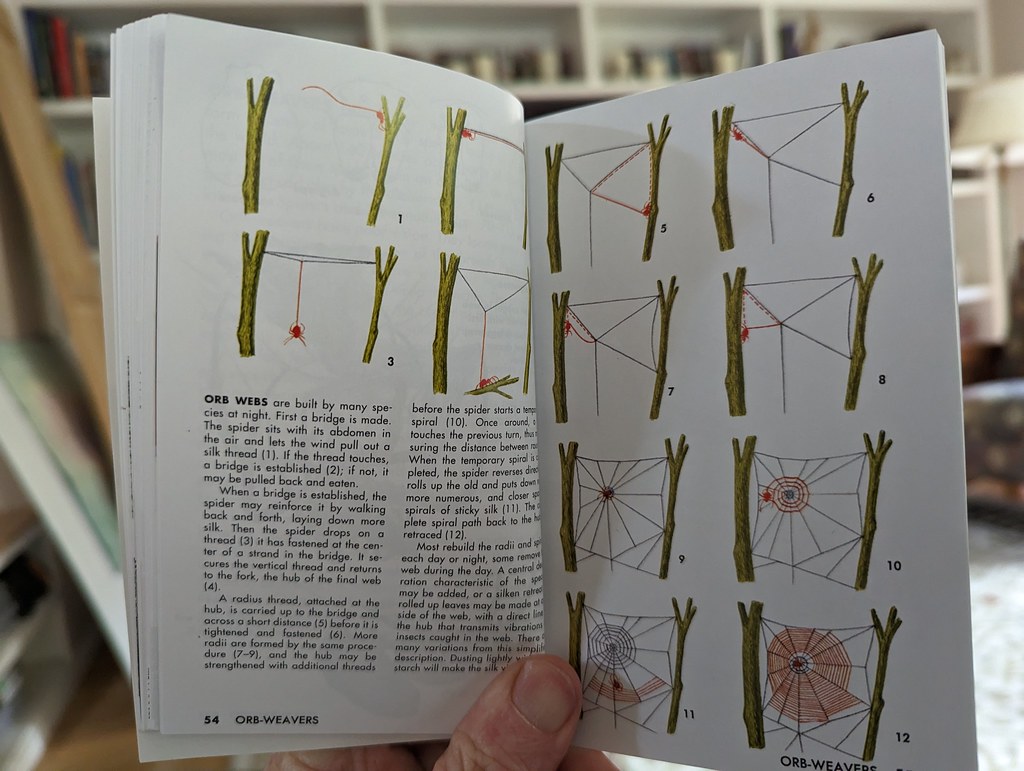

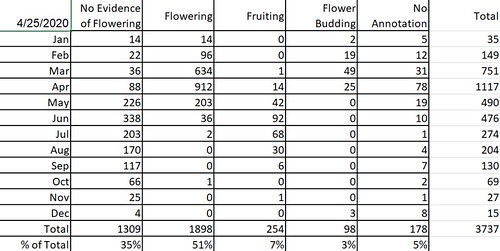

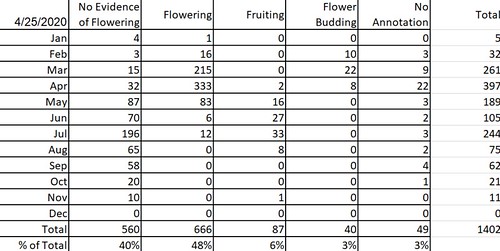

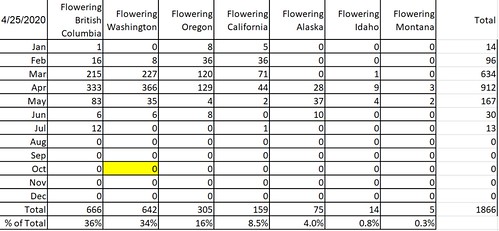

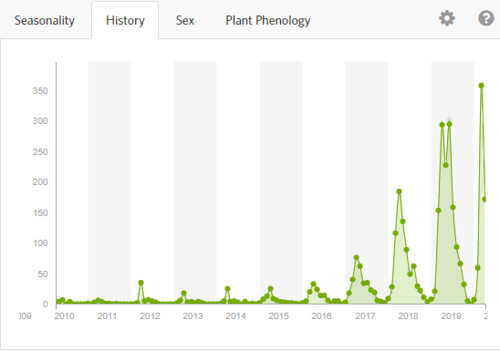

The book's core is an illustrated review by family of spiders, spider relatives, myriapods, and land crustaceans. It has worldwide coverage. The length of each section varies based on the number of species. For example, orbweavers (Araneidae) cover 19 pages, about 12% of the book. One of my favorite spider observation was an Araneus diadematus (Cross Orbweaver). This spider has taken up residence in a sheltered corner near the front door of my house. I named it Ardi2020. Here's some observation of the same spider, I saw it almost every day:

16 March 2020 25 April 2020 5 May 2020 7 June 2020 I watched this spider maintain its web over several months. Thus, I was happy to find a simple explanation on a two-page spread on how orbweavers build their webs.

The unit on wolf spiders (Lycosidae) helped me understand the behavior of the genus Pardosa. It was just a few sentences but it was useful. If I had looked in this book while making my observation, I might have got my ID to the genus level and realized that species ID was going to be a challenge.

This book will sit beside me while working on my iNaturalist observations of spiders and their relatives. It's a good introduction in 160 pages. One caveat is that this isn't a detailed species identification guide but should be helpful to classify down to the family level.

Thanks to Rod for taking the time to help an amateur naturalist improve.

Usá ArgentiNat con app iNaturalist

Usá ArgentiNat con app iNaturalist